The trends behind the historically low U.S. birth rate

This week, correspondent Jon Wertheim reported from Japan, the land of declining sons and daughters.

Over the last 15 years, the East Asian country has seen its population decline, amid low birth rates and falling marriage rates.

Last year, more than two people died for every baby born in Japan, a net loss of almost a million people.

60 Minutes reported on efforts by the Tokyo government to reverse this: shortened workweeks for government workers and a citywide dating app, both initiatives aiming to encourage people to get married and start families.

A young leader was elected to the Japanese Parliament last year; her campaign centered on transforming rural areas—where there have been diminishing economic opportunities—into viable working and living environments for young families. She believes revitalizing the countryside will help ease the population decline.

While these efforts are just the latest attempts to address demographic issues, previous attempts by the government have not made a significant impact on the country’s fertility rate.

Wertheim told 60 Minutes Overtime that, in some ways, Japan is a “canary in a coal mine.”

“This is a real barometer of what a number of countries, the United States included, is going to confront in terms of demographics in the next decades and even centuries,” he said.

In fact, like Japan, the United States has seen its birth rate steadily decline over the last 15 years.

On Wednesday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that the total fertility rate was 1.6 children per woman in the United States, or 1,626.5 births per 1,000 women.

That is a less than 1% increase from 2023— a year that marked a record low, and well below the total fertility rate of 2.1 needed to naturally maintain the population.

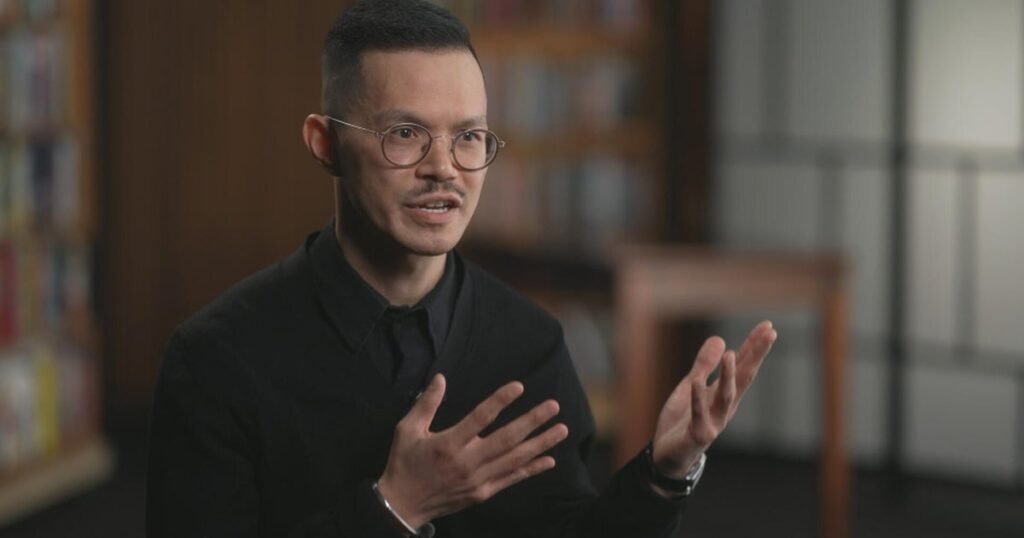

60 Minutes Overtime spoke with Dr. Thoại Ngô, chair of Columbia University’s Heilbrunn Department of Population and Family Health.

“The big data story from the CDC data is that women under the age of 30 are having less babies,” Dr. Ngo explained.

“Teenage pregnancy has been declining and… [there’s] a macro-societal shift on how people value family, work, and personal fulfillment moving forward.”

Breaking down the data

The recent CDC data shows the birth rate of teenagers between 15 and 19 dropped from 13.1 to 12.7, part of a long downward trend that started in the 1990s.

60 Minutes Overtime also spoke with Dr. Karen Benjamin Guzzo, director of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina.

Guzzo said the largest contributing factor to the decline in teenage pregnancies is the increased use of more effective contraception.

“The United States has always had much higher rates of teen and unplanned pregnancies than other countries,” Dr. Guzzo explained.

“This is a success story… that people are able to avoid having births early on, when they themselves would say, ‘This is not the right time for me.'”

But taking overall trends into account, American women between the ages of 20-29 are also having fewer babies, and may be opting out of having children altogether.

Dr. Kenneth M. Johnson is senior demographer at the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of New Hampshire.

In an interview, Dr. Johnson said finding out what’s happening among this particular age group is the “big question” and many factors are at play.

He pointed to one trend that could explain part of it: many young women are delaying marriage, and a significant share of that group is delaying having children.

And within those marriages, the time taken between marriage and childbirth is now longer than it has historically been.

“In a sense, it’s just pushing everything further out,” he told 60 Minutes Overtime.

And despite more women in their late 30s having children, “it’s not making up for fertility declines among younger women,” he said.

“What’s coming to appear is that a lot of these babies are just going to be forgone entirely. They’re not going to be born.”

A fear of economic decline

The worrisome scenario for countries who face low birth rates is a small young population and a much larger elderly population.

In theory, a smaller young population would not be able to contribute to the workforce, attend schools and universities, pay for goods and services, pay taxes, start businesses and create economic growth at the level that the previous generation did, since there would simply not be enough people to contribute at the same scale.

In that scenario, institutions used to larger amounts of young people, like hospitals, schools, and businesses, wouldn’t have the number of patients, students and customers needed to maintain growth. And that could create economic decline and unemployment due to reduced demand.

Dr. Ken Johnson of the University of New Hampshire described a scenario feared by universities called the “demographic cliff.”

“Right now, [the demographic cliff is] a big worry at the university level, because the amount of young people is declining,” he told Overtime

Dr. Johnson explained that babies who were born in 2008, when the birth rate first started to decline, are now 17 years old and matriculating into college.

And the gap between how many babies would have been born, based on the birth rates then, and how many were actually born has already started to widen.

“There will be 100,000 fewer kids than there might have been who reach the age of college freshmen next year, and the gap will widen to 500,00 a year in three years and nearly a million a year in ten years,” Dr. Johnson said.

Another concern is Social Security and elder care, which arguably requires a proportionate young population to take care of the elderly population.

“Young people are paying tax into the system so that it can keep the [Social] Security system up and running for the older generation,” Dr. Thoại Ngô of Columbia University told Overtime.

“But it’s also the young people [who] are meant to take care of the older generation.”

Trump administration hearing proposals

The Trump administration is listening to proposals that would encourage more people to have children.

Some of these ideas include financial incentives like a “baby bonus” for new mothers and an expanded child tax credit that would reduce the tax burden on new families.

But Dr. Ngô thinks cash incentives are unlikely to have a significant impact on the U.S. fertility rate.

“I think the global evidence is very clear: we can’t buy fertility,” he told 60 Minutes Overtime.

“Japan [has] invested so much in the last 40 years, and their fertility [rate] is still at 1.2…South Korea [has] invested $200 billion into boosting up fertility, and it hasn’t worked. Their total fertility rate is at 0.7.”

The University of North Carolina’s Dr. Karen Benjamin Guzzo explained that the state of the economy and a hopefulness about the future are stronger influences on would-be parents.

“People really need to feel confident about the future… having kids is sort of an irreversible decision and it’s a long-term one,'” she explained.

She said the Trump administration should take a closer look at solving the difficulties and expense of child care.

“We have child care deserts in the United States where you cannot find affordable, accessible childcare in a reasonable distance,” she said.

“[If] you’re in major cities… you’re talking like $1,400 a month in child care and there’s a nine month waiting list.

“We don’t have sufficient child care infrastructure. That’s where we should be building.”

The Trump administration has also issued an executive order that aims to make IVF treatments more accessible for those who can’t afford them.

Dr. Thoại Ngô is optimistic that affordable IVF treatment would have an impact and allow couples who want children to do so more easily.

“Lowering the cost of IVF is great for a couple who wants to have babies. And I think we have to do it in a fair way… all couples who want [a] baby should have access to that.”

Finding demographic solutions

Fertility rates and birth rates are helpful indicators to understand where a population may be heading, but these statistics only focus on births.

Population change is also influenced by mortality, immigration, technological advancements and many other social, economic, and technological factors.

“Not everybody is going to like it, but… immigration, technology, and education can all help keep the economy dynamic,” Columbia University’s Dr.Thoại Ngô told Overtime.

“The rise of AI [will] replace a lot of mundane and repetitive jobs… it opens [the] door for investment in training, and education in quality jobs, in enjoyable jobs.”

UNC’s Dr. Karen Benjamin Guzzo believes that immigration could make up for future shortfalls in labor.

“Our health care industry actually uses quite a bit of immigrant labor… they’re often willing to work in places that are rural, where it’s harder to get [Americans] to live.”

Dr. Ngô said a reallocation of resources, a supportive set of policies and programs, like paid family leave and better child care, and a strong economy could allow all parents to have a child more easily, without worrying about the financial stress.

“Better health care, economic stability, and a more thriving set of [policies could] allow people to have a freedom of choice in terms of what kind of life they want for themself.”

The video above was produced by Will Croxton. It was edited by Sarah Shafer. Jane Greeley was the broadcast associate.

You may be interested

Fuerza Regida ‘Manifested’ Making History on Billboard 200: Exclusive

new admin - May 13, 2025[ad_1] Fuerza Regida made history on the Billboard 200 chart this week. The band’s 111XPANTIA is now the highest-charting Spanish-language…

Tory Lanez attacked in prison while serving time for shooting Megan Thee Stallion

new admin - May 13, 2025Tory Lanez attacked in prison while serving time for shooting Megan Thee Stallion Tory Lanez attacked in prison while serving…

Noname’s SummerStage Show Is Canceled

new admin - May 13, 2025[ad_1] One week after the organizers of New York City’s annual SummerStage concert series canceled R&B singer Kehlani’s Pride show…