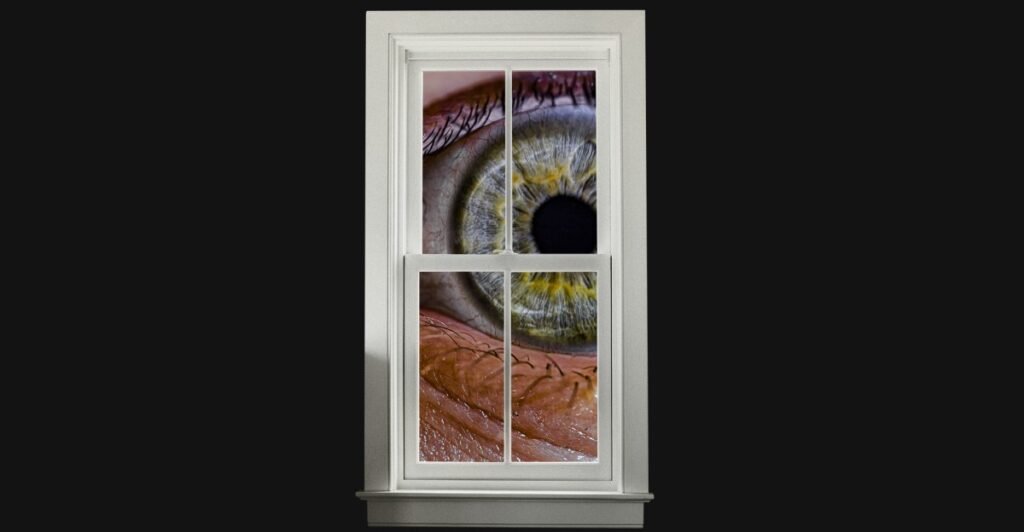

America desperately needs new privacy laws

This is The Stepback, a weekly newsletter breaking down one essential story from the tech world. For more on the dire state of tech regulation, follow Adi Robertson. The Stepback arrives in our subscribers’ inboxes at 8AM ET. Opt in for The Stepback here.

In 1973, long before the modern digital era, the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) published a report called “Records, Computers, and the Rights of Citizens.” Networked computers seemed “destined to become the principal medium for making, storing, and using records about people,” the report’s foreword began. These systems could be a “powerful management tool.” But with few legal safeguards, they could erode the basic human right to privacy — particularly “control by an individual over the uses made of information about him.”

These concerns weren’t just cheap talk in Washington. In 1974, Congress passed the Privacy Act, which set some of the first rules aimed at computerized records systems — limiting when government agencies could share information and outlining what access individuals should have. Over the course of the 20th century, the Privacy Act was joined by more privacy rules for fields including healthcare, websites for children, electronic communications, and even video cassette rentals. But over the past couple of decades, amid an explosion in digital surveillance by governments and private companies, Congress has repeatedly failed to keep up.

Lawmakers have weighed numerous plans for preserving Americans’ privacy, yet over and over, they’ve fizzled. Attempts to rein in government spying — like proposed updates to the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 — have been sandbagged by fears they’d compromise police and anti-terrorism operations. Despite multiple concerted attempts from members of both parties, Congress hasn’t passed a bill that governs how private companies collect data and what rights people have over their own information. Even highly targeted proposals like the Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act — which restricts police from bypassing existing privacy laws by using data brokers — haven’t cleared the hurdle of becoming law.

Meanwhile, new technologies, from augmented reality glasses to generative artificial intelligence, create fresh risks every day — making it easier than ever to surreptitiously surveil people or encouraging sharing intimate information with tech platforms.

Immigration agents are harassing citizens that they’ve identified with data analytics tools and facial recognition. Data breaches at major tech companies are common, and security regulations meant to prevent them are being rolled back. Amazon just aired a Super Bowl ad bragging about how your doorbell can become part of a distributed surveillance dragnet for finding dogs.

At every point, invasions of privacy don’t just risk revealing something intimate about you to the world, they shift the balance of power toward whoever holds the most data. Take algorithmic pricing, where companies use personal information about shoppers to set individualized prices they estimate people will pay — resulting in companies like Instacart charging users different prices for the same item. (The company said this was an experiment it’s since ended.)

State-level and international regulations have addressed some privacy risks. Companies in Europe have been governed by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) since 2018, though a rollback was proposed late last year. Several states have passed some form of general privacy framework, as well as more specific rules — Illinois’ biometric privacy law has facilitated lawsuits against Meta and others, for instance, and New York mandated algorithmic pricing disclosure a few months ago. However, privacy advocates warn many of the rules are inadequate. The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) and US PIRG Education Fund graded state consumer privacy bills in 2025, and only two states, California and Maryland, earned higher than a C.

EPIC deputy director Caitriona Fitzgerald tells The Verge that Congress has passed at least one meaningful reform lately: the 2024 Protecting Americans’ Data from Foreign Adversaries Act, which Fitzgerald calls “the strongest privacy law to be passed at the federal level in recent years.” PADFAA bars data brokers from letting hostile nations access sensitive personal information of Americans, and EPIC used it to file a complaint against Google’s real-time bidding ads system — which it alleges broadcast sensitive data indiscriminately.

Overall, though, it’s fair to say the situation isn’t great.

As of early 2026, in many places, a sense of learned helplessness around privacy has taken hold. Companies like Meta push the line that if an existing technology already poses privacy concerns, it’s unreasonable to complain that a new technology does it even worse. According to internal documents, Meta also apparently believes that the Trump administration’s highly public flouting of civil liberties (or what Meta euphemistically deems a “dynamic political environment”) will keep activists distracted, leaving it free to push invasive features like facial recognition into products.

But the administration’s actions are making the dangers of these systems more and more difficult to ignore. It’s one thing to know the government could look up personal information about you. It’s another to have ICE agents intimidate you by dropping your name.

Not all of today’s privacy nightmares have easy regulatory solutions. But privacy groups have said for years that there are obvious ways to start improving the situation. A long-standing wishlist from a coalition that includes EPIC, PIRG, and others suggests creating a new independent federal Data Protection Agency, as well as a private right of action that would let individuals sue over violations of privacy laws. One of the most recent proposals is the Data Justice Act, a piece of model legislation outlined last month by a group of scholars at NYU Law. It’s aimed at limiting state collection and use of our deep digital footprints, aiming to redefine personal data “not as information the state may freely access, but as something inherently ours.”

There’s likely no turning back the clock on many digital technologies — nor, in many cases, would people want to. But it’s past time for more lawmakers to take the risks these technologies create seriously and decide it’s worth fighting back.

- In many ways, governments across the world are actually going backward on privacy, thanks to the rise of online age-gating. In the US, the Supreme Court has already okayed age verification for sites with a large volume of adult content. Now, multiple states have passed laws that require it for essentially every app on your phone, a policy the Supreme Court seems likely to consider sometime this year.

- Virtually every problem in tech regulation is intertwined, so tech monopolies also exacerbate privacy problems by reducing competition and concentrating information in a few places where it can be exploited. (That’s another issue Congress has taken up but failed to follow through on.) Also, laws don’t work if the government won’t fairly enforce them, so the Trump administration’s era of gangster tech regulation needs to end.

- One of the simplest rallying cries for privacy in recent years is “ban facial recognition” — typically from use by government and law enforcement, but there’s a push to limit its rollout privately on smart glasses, too.

You may be interested

AJ Edelman speaks out against Olympic broadcaster’s anti-Israel tirade

new admin - Feb 22, 2026[ad_1] NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles! Team Israel Olympic bobsled captain AJ Edelman has accomplished a life…

BAFTAs red carpet 2026: All the fashion as Hollywood stars arrive for ceremony | Ents & Arts News

new admin - Feb 22, 2026As well as the film prizes, red carpet fashion is also a huge part of any awards ceremony.Emma Stone, Kate…

Remembering The Rev. Jesse Jackson, an American original

new admin - Feb 22, 2026In 1988, the Reverend Jesse Jackson ended his outsider campaign for president with a stirring speech for the history books:…