Will Stancil is agitating in Minneapolis

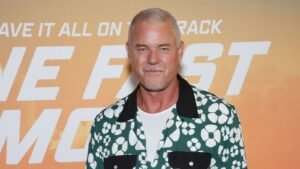

I met Will Stancil two days before he got booted from his neighborhood Signal chat. We were at the Uptown Minneapolis VFW at an event hosted by Rep. Ilhan Omar, a thank-you party for Minnesotans who fought ICE in ways big and small. There were tacos and drinks, and dancing, though I never saw Stancil dance, which is not to say it never happened. A friend of mine who knows of Stancil from his work on school desegregation was surprised I knew who he was. She had no idea he was a combative, divisive online personality. She didn’t know about his arguments with leftists on Bluesky or his fights with white supremacists on X, or about the fact that some of Stancil’s erstwhile opponents have, in light of his new proclivity for chasing and getting tear-gassed by ICE, begrudgingly accepted him as a sort of antihero.

When I approached Stancil, who is almost shockingly boyish-looking in person, he was talking to former New York City comptroller Brad Lander. He had flown to Minneapolis that day to learn about the local response to a federal occupation. Stancil offered to let Lander tag along on one of his ICE patrols — a practice locals now call “commuting” — and said I could join them if I wanted. It’s this openness to media attention that got Stancil kicked out of the Signal group, where many commuters are wary of press, hoping to not draw too much attention. Stancil has talked to, and in some cases been joined by, reporters from CNN, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, The Economist, the Guardian, the Financial Times, the Minnesota Reformer, Racket MN, Mpls. St. Paul Magazine, the Toronto Star, and now The Verge.

For Stancil, the goal of commuting is to create a record of ICE’s abuses. Armed with a phone camera while federal agents are armed with weapons, he’ll record arrests in progress — what everyone now calls “abductions” — and agents’ often violent reactions to being observed. He has taken pepper spray and tear gas to the face on numerous occasions, most of which he has recorded and posted about after the fact. Stancil’s critics, however, think that in making himself a spectacle, he’s putting everyone else at risk. Two major charges have been levied against Stancil. The first is that he’s in it for the attention, perhaps to boost his profile if he runs for office again. (Stancil unsuccessfully ran for State House in 2024. “I’m not saying, ‘Look at me!’ It’s really not about that,” he told me.) The second is that he’s practicing bad OPSEC, not only endangering himself but other members of his community.

He really wanted to talk about the Signal chats

So he was banned from the Signal chat the night before I was scheduled to engage in that rite of passage for out-of-state journalists who had parachuted into Minneapolis: a ride through the neighborhood in Stancil’s Honda Fit. Stancil was apologetic, but more importantly, he was aggrieved. We quickly worked out other arrangements. He was allowed into the Southside Signal group, which has a more open media policy than the Uptown chat from which he’d been ousted. The moderators had asked him to send me a press agreement beforehand. I promised to keep all statements made on the call off-the-record and not to record audio or video of the chat.

I met Stancil before sunrise the next morning, along with Jack, my photographer who had been in Minneapolis for an action-packed two weeks. The city was just waking up. I saw few people on the street on the short drive from the cultural void that is Downtown Minneapolis to Stancil’s apartment Uptown, and most of those I saw were, I assumed based on their neon safety vests, school patrollers. Stancil was waiting for us, idling in his gray Honda Fit. He really wanted to talk about the Signal chats.

“They said, ‘You broke the rule. The rule is no press ever.’ I said, ‘No one’s ever told me that rule before.’ Then they said, ‘You discussed publicly that you were getting kicked out, and that’s breaking the rules.’” Stancil asked for an appeal. The response, he said, was a shrug emoji. The opacity bothered Stancil. So did the way some of his fellow commuters — his neighbors! — were treating this whole thing. “It’s not a guerrilla organization,” he said. “People want to run it that way, all secrecy and cloak-and-dagger, but the reason it works is because there’s so many people doing it.”

We were in unfamiliar territory. That this wasn’t Stancil’s turf was clear. At one point, he took a left when he should’ve taken a right, and Jack had to tell him Cleveland Avenue was actually the other way. A few minutes later, Stancil went the wrong way down a one-way street, accidentally maneuvering us into oncoming traffic. Stancil’s driving was, for the most part, erratic. He pushed the Honda Fit to its limits, speeding to beat yellow lights and running red ones. “It’s a very Minneapolitan thing,” he told me, “to be like, ‘I’m chasing a federal agent but there’s a yellow light. Oh no, I have to stop!’”

Minnesotans are a polite, rule-following bunch, and they regard traffic laws with quasi-religious reverence. When I visited in 2024 for the state fair, I was simultaneously shocked and delighted by multiple pieces of seed art dedicated to one highway adage: “merge like a zipper, you’ll get there quicker.” ICE agents were identifiable by their disregard for the rules of the road, to make no mention of their unfamiliarity with wintry streets. But commuters had started driving erratically, too — Stancil especially. How would they ever catch up to ICE otherwise?

It was a slow day. We drove around Southside for an hour, maybe an hour and a half, and ICE sightings across the neighborhood were sporadic. There was none of the action Stancil had grown accustomed to seeing. On a ride-along with a reporter a week earlier, Stancil had run into ICE almost immediately after getting on the road and was tear-gassed within minutes of exiting the car. We were, depending on how you look at it, either lucky or unlucky. We drove and drove and nothing happened, giving Stancil plenty of time to talk about previous interactions he’s had with ICE, arrests he’s witnessed, and, of course, about his ejection from the Signal chat.

“I know for a fact people who previously hated each other’s guts and are now working together”

Every few minutes he’d interrupt himself mid-sentence to listen to the Signal call or focus on a particularly ICE-looking car. An SUV with tinted windows aroused suspicion until we saw the driver: he was alone and smoking a cigarette, so he probably wasn’t a fed. Stancil told me about a Chevy Silverado he’d seen on the street that was “a confirmed ICE vehicle” despite being “highly unconventional.” He had seen it again the previous day while commuting with Brad Lander, who got out of Stancil’s car to greet the two men sitting in the Silverado. “And they just go roaring out of there,” Stancil said, but not before Lander saw the tactical gear they had on. “They’re trying to scope people out or something, because we saw them over and over.” He wanted to see them again today. He wanted to figure out what they were doing. The Silverado was Stancil’s white whale and he was desperate to find it.

We drove past a van that had “NOT ICE” written on it, which could either mean it definitely wasn’t ICE or absolutely was. Agents had reportedly been disguising their cars — adding bumper stickers, installing bike racks — to throw off observers. All this subterfuge had created a culture of paranoia in the Twin Cities and with good reason. Federal officials accused both Renee Good and Alex Pretti of being “domestic terrorists” and suggested that anyone involved in any kind of anti-ICE activity is part of a coordinated criminal operation. Dozens of people have been arrested, some on federal charges, and it’s likely that more are coming: the Department of Homeland Security subpoenaed Google, Meta, Discord, and Reddit, asking for the names, email addresses, phone numbers, and other information of people who have been tracking ICE.

Will Stancil the person is not dissimilar to Will Stancil the internet personality. Both are frenetic, jumping from topic to topic with an intensity that despite its effortlessness cannot be described as ease. Where Stancil’s online persona seemingly delights in picking and escalating fights with his many critics, the flesh-and-blood Stancil is affable if not necessarily charming. He proffered a kumbaya-esque description of the city’s response to the federal occupation: before ICE came to town, Minneapolis was beset by “horrible factional infighting” between leftists, liberals, and moderates. Now everyone has set their differences aside to vanquish a common enemy. “I know for a fact people who previously hated each other’s guts and are now working together,” he said.

He told me about someone he knows “high up on the moderate Democrat side of things” whose posts now read as if they were written by a member of the Democratic Socialists of America.

“Even with me,” Stancil said, “I’ve had people come to me like, ‘You know, I’ve said some things [about you].’ And it’s like, I don’t care. Who cares? I don’t even remember. Set it aside. That’s been nice to see. Hopefully it sticks. It’s been genuinely inspiring to see so many people come together.”

This newfound sense of unity has its limits. Stancil, after all, was removed from the group chat, a point he returned to again and again in our conversation. “One reason I’m a little sad about getting kicked out of the group, and this is corny as all get out, is that there’s something about, they’re coming for my neighbors. They’re coming from my part of town. Over here, the people I see on the street are people I know. Over there, I don’t know them. That’s a really special thing that’s getting a lot of people up in the morning.”

Stancil is exceedingly earnest. He canceled a doctor’s appointment to spend the morning tailing ICE, even in this unfamiliar neighborhood. His outrage at the federal occupation of the Twin Cities is palpable, and in this he is no different from other left-of-center Minnesotans whose politics aren’t exactly radical — he is in some ways, in fact, further to the left than the “Edina wine moms,” in the words of one organizer I met, who have recently found themselves joining the cause — except those other liberal-but-not-leftist Minnesotans tend to keep a low profile both on- and offline, and therefore aren’t getting into fights with socialists and anarchists over things like OPSEC and the efficacy or futility of talking to the media.

Perhaps because of his outsize internet presence, Stancil’s removal from the Signal chat sparked a weeks-long discourse cycle on Bluesky and X that appears to have no end in sight. Throughout it all, Stancil has doubled down. The occupation may have brought together liberals, leftists, and anarchists, but only to a point.

Both on- and offline, people have argued over whether Stancil’s penchant for posting through it — a tendency his supporters consider openness and his detractors consider exhibitionism or perhaps self-centeredness — is detrimental to the cause. The discord has bled out into real life. Some locals I met told me they didn’t have a problem with Stancil letting journalists join him; they had indeed taken me commuting with them. Other organizers told me his antics put everyone at risk. One source said they’d retract their interview if it appeared in the same piece as Stancil’s. And in early February, the week after Stancil and I met, a video circulated online of someone punching Stancil. It’s unclear what led to the confrontation, but the video shows a small group of masked people surrounding Stancil, who mocks his soon-to-be attackers. “Shut up, man. I’ve done so — I’ve done a lot more than you have,” Stancil tells them. “Shut up. Jackass.”

“One thing you’ll hear a lot in left-wing circles is that this proves community policing works,” Stancil said of ICE watches. “I would say the opposite. This is exhausting, inefficient, there’s a lot of false positives, a lot of people get away. It requires massive resources. But we’re only doing it because more traditional mechanisms have broken down here or aren’t available for us. And it has worked because of the scale of it, but you can’t have 5,000 people a day randomly patrolling their neighborhoods. In the long-term, it’s not viable.”

This was one of those slow days that made the whole thing feel futile. We drove in circles in search of ICE and saw nothing, a stillness that implied they were active elsewhere, in another neighborhood or a nearby suburb, even if they weren’t here.

And then he saw the Silverado. I noticed it before he did but wasn’t sure it was the same car — the one he described was green, and this one was a sort of blue, so I said nothing. The Silverado turned left and we turned right and that’s when Stancil saw it. We were in backed-up traffic on a busy two-way road, which Stancil pulled a U-turn in the middle of to get us where we needed to be. The Silverado sped through a light we couldn’t run without getting T-boned, so we waited impatiently as we watched it get away. When the light turned green, Stancil cut off another car in an attempt to catch up. “He’ll think I’m awful rude,” he said, “but that’s okay. I can live with that on my conscience.”

You may be interested

Possible next steps after the arrest of former Prince Andrew

new admin - Feb 20, 2026LONDON — Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor may have been released from custody, but his legal saga is not over.On Friday, police continued…

U.S. and U.K. to discuss use of Diego Garcia base as Iran protests Trump’s threat to use it in an attack

new admin - Feb 20, 2026U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio and his British counterpart were to meet Friday in Washington amid tension between the…

U of Louisville to Close On-Campus Preschool

new admin - Feb 20, 2026[ad_1] University employees say the early childhood learning center was the most significant family-friendly benefit on campus. Nimito/iStock/Getty Images Plus…