Why One AI Administrator Is Skeptical of AI

Three years after generative artificial intelligence technology went mainstream, predictions about how AI will transform the workforce and learning haven’t slowed down.

Last year, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei predicted AI could wipe out half of entry-level white collar jobs within just five years. More recently, Mustafa Suleyman, Microsoft’s AI CEO, forecast an even gloomier outlook: Most white-collar tasks “will be fully automated by an AI within the next 12 to 18 months.”

At the same time, universities across the country are scrambling to prepare their students for a workforce that’s increasingly reliant on AI. Many, including Ohio State University, the California State University system and Columbia University, are trying to accomplish that in part by partnering with mammoth tech companies, such as Google and OpenAI, that claim their products will also enhance learning and instruction.

But Matthew Connelly, a professor of history and a vice dean for AI initiatives at Columbia University, is skeptical of the higher education sector’s rush to partner with tech companies without much proof that their AI tools improve learning outcomes. Instead, he believes such partnerships are offering tech companies training grounds to create the very AI systems that could replace human workers—and usurp the knowledge-creation business higher education has long dominated.

“Young people are quickly becoming so dependent on AI that they are losing the ability to think for themselves,” Connelly wrote last week in a guest essay for The New York Times titled “AI Companies Are Eating Higher Education.” “And rather than rallying resistance, academic administrators are aiding and abetting a hostile takeover of higher education.”

Inside Higher Ed interviewed Connelly about what’s driving his skepticism.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Q: What does your job as a vice dean for AI initiatives entail?

A: A lot of things. For one, we are doing what may be the world’s largest randomized controlled trial of undergraduates in a writing course, where we’re trying to find out how we can encourage them to use AI ethically and effectively and how we can prevent them from misusing it in a way that will undermine learning. We also do a lot of work on curricular review, such as working with departments on whether they need to change the way they teach courses.

Q: Before you took on that role, how had you used AI-powered technology in your work as a historian?

A: For the past 15 years, I’ve been working with data scientists, computer scientists and statisticians to use machine learning and natural language processing to explore history in a way that is both new and increasingly necessary. Historians are overwhelmed with data, and the way we were trained to do our work—going to an archive and looking through paper files—is going away. I’m working with colleagues to try to come up with new approaches where we can take advantage of the incredible strengths of artificial intelligence to help us do better, more rigorous historical research.

But while there’s lots of talk about what AI can do, when you sit down and you actually do research [on those claims], it turns out that a lot of the potential for AI is only potential. There’s a big gap between what people say is possible and what proves doable when you actually try to do it in a controlled setting.

Q: What’s driving your skepticism of the tech sector’s claims that their AI-powered tools have the power to transform teaching and learning?

A: We’ve been here before. For example, a lot of us remember talk about how open online courses were going to put some versions of higher education out of business. But then all of us got to experience open online courses during COVID, and many of us realized that it was a really inferior experience to in-person instruction.

For decades, the people pushing education technology have claimed their products will solve all of higher education’s problems, make everything cheaper and lead to dramatic improvements. But what the research has found over and over again is that these tools often have a negative effect. In some cases, one might have a modest positive effect, but you have to weigh that against the costs or other unintended consequences.

Why should we trust that AI-powered tools will be any different when people pushing education technology have been proven wrong over and over again? The onus should be on them to show us rigorous research that demonstrates real improvements from AI adoption.

Q: How have you seen the widespread adoption of AI tools both support and weaken critical thinking in students?

A: AI can indeed support more rigorous learning, but only in ways where you have students working alongside professors and testing what’s possible. It’s a lot of trial and error. It doesn’t help if, instead, large numbers of students are using AI without any kind of instruction, testing or research that shows what kind of work is useful at scale.

It’s always been a challenge trying to get students to get something deeper from their learning experience than a piece of paper at the end, but it’s so much harder when technology suddenly allows them to get the grades they want without doing anything. We’re trying to train future scientists and engineers, but these AI companies are making it increasingly difficult. It’s like they’re eating the seed grain.

Q: Why do you believe so many higher education institutions are scrambling to partner with tech companies to adopt AI tools despite limited evidence to support their effectiveness?

A: Many institutions are thinking that if they don’t make AI available to our students, then they’re not going to be prepared for the workplace. That is a scary place to be. You don’t want to be the one place that says you’re not using AI because we don’t know that it actually is going to help learning when all of your competitors are adopting AI at scale.

Q: What are some of the threats that you think these AI partnerships pose for the higher education sector?

A: It’s insulting when these companies claim their products can function at the level of Ph.D. students when the only way that’s possible is systematic theft—the theft of the intellectual property of countless academics.

And although a lot of these agreements say these companies aren’t supposed to use our data for their training, the only data we’re given is very high-level usage data, like how frequently people in our community log in to the program. We don’t know how people are using these systems.

For example, students could feed their classmates’ papers into Gemini and ask it to generate responses and criticism that they could pass off as their own. Faculty may be doing the same thing if they use one of these programs to help grade student papers. And that means someone’s work has been fed into these systems without permission and these companies may be appropriating it.

Right now, it’s like the Wild West. People could be using these systems in any way they want.

Q: What can the higher education sector do to defend its role as the epicenter of knowledge creation and rigorous intellectual inquiry?

A: We have to come together. No one institution can do this by themselves.

There’s a huge opportunity for the first leader in higher education to stand up and say, “We stand for human intelligence and we’re not going to help trillion-dollar companies develop the technology that’s going to allow employers to use AI instead of hiring humans.” We have to make clear that we stand for human intelligence and we’re only interested in AI to the extent that it can help make people more intelligent.

We have to start defending our own intellectual property.

You may be interested

Google Pixel 10A preorders come with a $100 gift card

new admin - Feb 18, 2026As promised, Google opened preorders for its Pixel 10A midrange phone, and it’ll launch on March 4th. We already published…

Fourth alleged rape victim testifies against son of Norway’s future queen: “He just wouldn’t stop”

new admin - Feb 18, 2026A fourth woman at the center of a rape case against the son of Norway's crown princess testified in an…

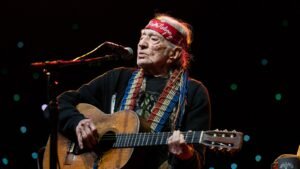

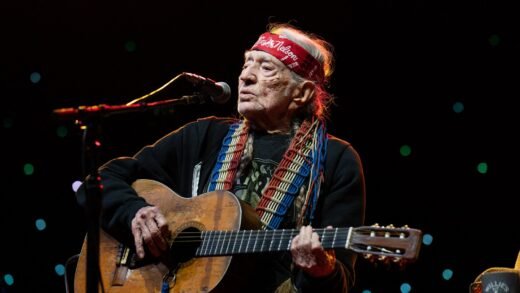

Willie Nelson, St. Vincent to Perform

new admin - Feb 18, 2026[ad_1] As Willie Nelson likes to say, “You’re either in Luck or you’re out of Luck.” On Thursday, March 19,…