How Bob Weir Came to Embody the Grateful Dead: Cover Story

A

t a recording studio in Woodstock, New York, Bob Weir was in the midst of making Blue Mountain, a 2016 collection of newfangled cowboy ballads that spoke to one of the Grateful Dead singer-guitarist’s passions, when he paused between takes. Turning to one of the studio’s employees, he said, “I need you to go to the hardware store. We’re going to need a 10 — make it a 15 — pound sledgehammer.”

Producer Josh Kaufman had dealt with plenty of requests from musicians in the past, but nothing quite like this. “We’re all like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’” he recalls. Everyone learned soon enough when the tool arrived. Stepping outside, Weir — in white yoga pants and a blue tank top, his hair and bushy beard pepper-gray — began carefully swinging the sledgehammer around his head and behind his back. As he told the crew gathered around to watch, that move was one of the oldest exercises known to man, and helped relieve lingering shoulder pain. “He had all these different moves he had memorized,” Kaufman says. “He seemed pretty in control. He had good balance.”

Everybody, it seems, has their Bob Weir exercise stories. On tour with Bobby Weir and Wolf Bros, a late-period side project, Don Was took a shot at the resistance ropes Weir would hook up to a tree on the side of a road. “He got too good for me,” says Was, the well-known producer who served as the band’s bassist. “I couldn’t keep up with him.” Footage of Weir training, released with his approval, became must-see memes. But Weir’s transformation into a late-in-life fitness guru, the Jack LaLanne of the counterculture, was more than a sight gag: It was a sign Weir was pushing hard, often physically, to come back from a devastating loss that almost derailed him.

Photograph by © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

For the first 30 years of his life in the Dead, Weir inhabited different roles. He was the youngest member of the original lineup, the voice behind some of the Dead’s friskiest songs (from “Sugar Magnolia” and “Truckin’” to “Estimated Prophet” and “Hell in a Bucket”), the prankster who got the Dead banned from a major airline by flashing a cap pistol and dropped a water balloon on a cop. Even with his unorthodox style of guitar, which blended lead and rhythm, Weir was the glue that helped keep the band together. “We tried to kick him out at one point, but it didn’t stick,” says drummer Bill Kreutzmann, referring to a contentious 1968 band meeting. “He just wasn’t having it. Instead, he knew that if he was going to last, he’d have to figure out a way to play guitar that complemented instead of competed with Jerry [Garcia]. And since Phil [Lesh] didn’t play bass like it was glued to the rhythm section, Bob found some room there and wedged himself into the spaces in between. That’s why he played guitar unlike anyone else.”

From his early ponytail to his later hot pants, Weir was also the Dead’s resident Haight dreamboat. As Dead historian, author, and former band publicist Dennis McNally notes, “You have to have one good-looking guy in a band.”

But by the time Weir died — on Jan. 10, at 78, from “underlying lung issues” following a battle with cancer (according to his family) — he had taken on an even greater and more unexpected role. When Dead & Company kicked off in 2015, Weir was no longer the skinny teenager trying to keep up with Garcia and Lesh, nor the frequent butt of band ribbing for his space-cadet side. “He was the custodian of the most important American rock band, and he just held it so beautifully,” says Aaron Dessner of the National, who recorded and toured with Weir about a decade ago. “And it wasn’t an act. He was the living, breathing personification of it.”

Onstage with Weir in Wolf Bros, Was witnessed Weir’s bond with Deadheads on a regular basis. “They fucking loved him, man,” he says. “You could see how much they appreciated all the experiences they’d had ancillary to this music. We used to do ‘Ripple’ as an encore every few shows, and he knew what that song meant to them and gave it his all every time. He was aware of the responsibility he had and was honored to tackle it.”

But for Weir to arrive at that point was neither effortless, nor a given. Following the death of one of rock’s most recognizable icons and his charismatic mentor, Weir had an elevated role thrust upon him — one he continually grappled with and had to evolve into, whether he wanted to or not. As Deadheads witnessed for themselves over the course of some difficult years, Weir went through his own variation of the five stages of grief, from a form of denial through a degree of acceptance (with a new physical regimen to accompany it). To use the title of one of the later songs he co-wrote for the Dead, life after Garcia had no easy answers, and posed plenty of hard questions.

Garcia and Weir onstage in 1976.

© Greg Gaar/Retro Photo Archive

Weir’s tour bus had just arrived at the Hampton Beach Casino Ballroom in Hampton Beach, New Hampshire, when the news started to spread: That day, Aug. 9, 1995, Garcia had succumbed to a heart attack while in rehab in California. Weir was on the road with RatDog, a low-key side project that allowed him to partake in covers of the blues and R&B songs he loved. Refusing to cancel his gig in Hampton Beach, Weir told the couple of thousand in attendance, “Our departed friend, if he proved anything to us, he proved that good music makes sad times better.” In addition to a few lesser-known Dead songs, he also played Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” and spoke a few words at a press conference after.

The entire Dead community was devastated that day, but Weir was especially shaken. “Jerry’s passing hit us all hard, of course, but it was Bob’s world that changed the most,” says drummer Mickey Hart. “His partner was gone — the sound that was always there when he played was gone. They both had stage fright, and they knew that being with each other canceled most of that out. They hung out together in the same onstage tent and yakked or played something during the break and before the concert. They felt comfortable in each other’s presence.”

Weir was also the first member of the Dead to return to the stage. “After Jerry died, I think we all came around to the idea that the music still belonged to all of us and any of us could do whatever we wanted with it,” says Kreutzmann. “It took me a few years to figure that out, but I think it took Bob about five minutes — he played a show in New Hampshire the very night Jerry died. That was also his way of processing it.”

After flying to California for Garcia’s memorial service, Weir quickly resumed his scheduled tour with RatDog. Matthew Kelly, who had met Weir in grade school and played with him in Kingfish and the first incarnation of RatDog, doesn’t remember Weir breaking down about Garcia in those days. “Bobby’s way of dealing with it would be different from other people’s,” Kelly says. “Bobby was most comfortable when he was onstage. So the best way for him to heal was to keep playing in whatever configuration it might have been. And that’s what he did.”

“Jerry’s passing hit us all hard,” Mickey Hart says. “But Bob’s world changed the most.”

To the puzzlement of Kelly and the other band members, though, that music rarely included Dead material, and at the start, Weir declined to recruit a lead guitarist to play similar parts to Garcia’s. “The rest of us in the band got in some talks with Bobby about that,” Kelly says. “He said, ‘The more you guys keep saying that, the more I’m going to dig my heels in.’ It was a bit uncomfortable, because the audience was very much expecting us to do that. The looks on their faces were disconcerting and troubling.”

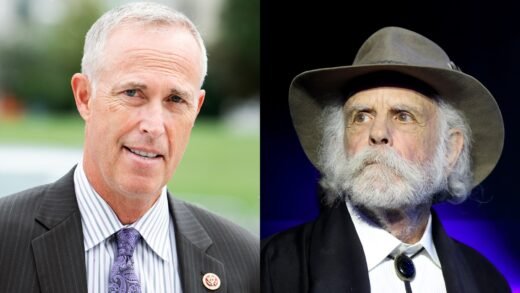

The looks grew even more puzzled when Weir, known as the most boyishly handsome member of the Dead, grew facial hair, prompting comparisons to a Civil War reenactor or the cartoon character Yosemite Sam. “The beard happened out of sheer laziness while I was on tour,” Weir later told Rolling Stone. “And after being lazy and not shaving for a couple of weeks, I decided I liked the look. I think that’s the way it happens for a lot of guys.” For McNally, the significance was deeper. In 1996, Weir, who’d been adopted, had reconnected with his real father, Jack Parber. One night, the two of them, along with McNally, took in a show together in San Francisco. “Jack looked at him and said, ‘That beard makes you look like your uncle,’ presumably a brother of Jack’s,” McNally says. “I heard that, and I went, ‘Bobby’s never going to shave that beard.’ Tell a guy who’s been adopted that he looks like he’s related to somebody? Forget it.”

Weir was always eager to share anecdotes about Garcia and their escapades. But playing songs associated with his close friend — the one who had invited the teenage Weir into the jug band that became the Dead — remained daunting. Once, when RatDog were soundchecking for a show in Albany, New York, Weir began working up his first version of “Days Between,” the elegiac ballad Garcia and Robert Hunter had written toward the end of Garcia’s life. “He was putting so much work into it,” says Matt Busch, his manager at the time. “You could just tell he was working on something that meant so much to him. He was treating it with that kind of reverence.”

As Weir began playing it, a dam burst. “He was crying while singing it,” Busch says. “There was a hush in the room. You could just tell how much Jerry meant to him, how much the song meant to him. It showed so much.” At the time, though, those moments seemed few and far between.

BACKSTAGE AT THE BILL GRAHAM Civic Auditorium in March 2010, Weir, in his customary sandals and T-shirt, took a few sips of red wine and prepared to go onstage with Furthur, the Dead offshoot he and Lesh had launched a few months before. “The Dead’s gonna do what the Dead’s gonna do,” he told Rolling Stone, talking about the mothership outfit. “We’ve got to sell tickets and not turn people off or disappoint them. We’ve got to fulfill some requirements.”

Weir with Ratdog

© Herb Greene

Three years after Garcia’s death, the surviving members of the Dead — Weir, Lesh, Hart, and Kreutzmann, along with sidekicks like Bruce Hornsby — began reconvening for tours, in various configurations. (Among the many guitarists recruited to step into Garcia’s incredibly large shoes was Steve Kimock, who recalls asking Weir for direction and hearing back, “You’re the fucking guy now. Do what you will or what you can.”) Weir stuck with RatDog, who were transitioning from bars and clubs to theaters. But whether it was the repertoire, the throngs of Deadheads eager to see them all play again, the larger venues or even the shared duties, the lure of the Dead was too strong to resist. As Weir told Rolling Stone in 2008, after the core four had reunited for a benefit for Barack Obama, “When I’m on the road with RatDog, it’s a 14-hour day of set lists, interviews, and stuff. I’m on all the time. It’s a little easier for me with the Dead. The other guys can take on those responsibilities.”

Weir was right, but those tours — whether billed as the Other Ones or the Dead — were a blend of old camaraderie and lingering friction between the members. His bandmates could sometimes still treat Weir as the kid, busting his chops when he would forget a lyric onstage, as he did at least once on a Dead tour in 2009. But Weir appeared to roll with it, and the idea of writing new material with Furthur — his and Lesh’s project, without Hart or Kreutzmann, who weren’t invited — appealed to his restless creativity. “That’s gonna be the next place we’re gonna go,” he said before the San Francisco show, a 70th-birthday celebration for Lesh. “For instance, today, for the first time at soundcheck, we weren’t practicing an old tune. We were kicking something around that will become a song. And it’s about time.”

“It took me years to realize the music still belonged to us. It took Bob five minutes.”

Rising above the intraband fray, Weir remained gentlemanly and affable. But backstage at the Graham Civic, and in other interviews during that time, he often came across as taciturn and burdened — especially compared with the other surviving Dead members, who could be jokey and wisecracking. Weir had never been averse to alcohol; among his many lifestyle rituals was burning off a night of wine with an intense morning run the next day. Kelly recalls Weir driving around Marin County’s twisty roads after a fair bit of consumption. “It was a miracle he never died,” Kelly recalls. “I’d be terrified: ‘Bobby, can you slow down?’ He’d go, ‘Yeah,’ and step on the gas.”

But something had to give, and it finally did in a very public way. When Furthur took the stage of the Capitol Theatre in Port Chester, New York, in 2013, Weir was already dealing with long-standing physical pain: “I’m going to have to have my shoulder replaced at some point,” he told Rolling Stone in 2008 — the result, he said, of years throwing footballs as part of his jock side. But as Deadheads watched in dismay, a clearly discombobulated Weir collapsed onstage.

Although Weir never specified, band members attributed it to Weir taking an Ambien pill instead of a painkiller for a shoulder injury. When Rolling Stone asked him in 2025 what he learned from that experience, he replied, “Take it easier on myself a little bit, and stuff like that.” Weir was back onstage two months after the incident, for a benefit in Marin, but the time came for him to address his issues, and he stepped away for an undetermined period. When the topic came up during an interview in 2014, the late John Perry Barlow, Weir’s longtime friend and songwriting partner, said, “He’s been taking a little personal time. I think he’s doing more or less OK.” The same year, Lesh told Rolling Stone, “Yes, it makes me very concerned. But what to do?” For a moment, few knew the answer.

The Dead in 1979

© Herb Greene

WHEN HIS CELLPHONE LIT UP in 2013, Josh Kaufman wasn’t sure who was ringing him at his home in Brooklyn — no caller ID. But it soon became clear: “Weir here,” came the same genial greeting so many had heard over the years.

Weir’s road to Blue Mountain, the album that would play a major role in his return, had started shortly before that call. A year earlier, Weir had collaborated with a slew of East Coast indie rockers, including members of the National, on two live sessions, one in honor of Garcia’s 70th birthday. When Weir told Kaufman and the musicians he wanted the music to have a “cowboy swagger,” Kaufman helped conceive of a Weir album that’d tap into his love of cowboy songs and country.

On that phone call with Kaufman, Weir grabbed a guitar and started singing snippets of campfire songs from his past, eagerly wanting to add new verses to some of them. “I didn’t feel starstruck anymore,” Kaufman says. “I just felt like, ‘Wow, this guy’s just like us.’ He’s way cooler than us, but he’s passionate and wants to look for something in this music still.”

Recorded over a two-year period, Blue Mountain, Weir’s first solo album since 1978’s Heaven Help the Fool, was a beautifully ambient collection of modern-day ranch-hand ballads, and Weir soon launched an accompanying tour. But as Kaufman and his collaborators saw with the sledgehammer, the musical rebirth was just one part of his recovery. On tour, Weir’s exercise gear, including resistance ropes, took up so much space in the bus that others on the tour had to stash their luggage in their own bunks.

Speaking with Rolling Stone in 2016, Weir noted some lifestyle changes that accompanied his workout regimen. “Oh, you know, I can’t drink like I used to,” he said with a wise chuckle. Was that an issue? “Well, it depends on who you talk to,” he said. “I’m not as serious about drinking when I sit down to drink as I used to be. When I was more concerned about knocking ’em back, I wasn’t focusing on the delights a good glass of wine had to offer.” (He also rolled with a question about how many pairs of Birkenstocks he owned: “Four or five. Two or three of those pair you won’t want to own. I don’t know why I keep them.”)

Weir’s second — or third — wind coincided with the renaissance of the Dead. In 2015, he’d participated in Fare Thee Well, the five-concert series that found the four surviving core members celebrating the group’s 50th anniversary. Weir appeared back in control, and when he walked offstage one of the nights in Chicago, he flashed a smile, as if remembering the thrill of playing stadiums. Around the same time, in a moment Hart now calls “mythic,” Hart, Weir, and Mayer met at the Capitol Records building in Los Angeles. Soon after, Dead & Company, with John Mayer acquitting himself in the Garcia role better than anyone would have thought, set sail. “Bob finally had a lead guitar and could relax a bit,” says Hart, “and this took the weight off of being the only lead singer or guitarist.” Weir, Hart says, was “clean and sober, and Dead & Company was the new frontier.”

As the new kid in the band, Mayer soon learned which cues to take from Weir. “Bobby and I had this wonderful push-pull where Bobby liked a certain demureness in the music,” Mayer says. “At that point in his life, he wanted to go into the song and a telling of the lyric and the song through subtlety. Early on, I was hitting it too hot, even when I knew I shouldn’t. When I would mess up, Bobby liked it. He would look over at me and do the cross-eyed shake of his head, and I think it made him feel like I was willing to sign that same contract everyone in that band had signed, which is ‘We’re going to mess up sometimes.’ He probably liked it more when I messed up than when I hit a three-point shot, because he knew the messing up humbled me.”

“You could tell how much Jerry meant to Bob,” says Weir’s former manager.

Combined with Fare Thee Well and Day of the Dead, the indie-all-star tribute of Dead songs that came a year later, the Dead — and their newly resurrected, been-there-survived-that frontman — were suddenly hip, paragons of Americana, self-reliance, and an indie spirit. For those who’d never seen Garcia onstage or only knew him as a figure from a distant past, Weir was now the living embodiment of the band, its vocal link to the past, its gravitas-steeped elder statesman. He was their Jerry, evidenced by the T-shirt vendors outside their shows who would sell shirts with only Weir’s face on them.

Weir also injected a sense of adventurousness into some of the members of Dead & Company, including former Allman Brothers Band bassist Oteil Burbridge. “I would think, ‘We’re going to work on these songs,’ and then Bob would do a 30-minute jam on something else we had no intention of working on,” Burbridge says, recalling the band’s rehearsals. “It might be frustrating at times when you’re like, ‘OK, we got to get these 12 songs done today,’ but you just have to let your life proceed by its own design, and amazing things would come out of that, too. I was like, ‘Just hop on, man, wherever you’re at — don’t try to have a plan.’”

Weir’s renewal was also evident to Denise Kaufman, a musician and yoga instructor he’d met during the earliest days of the Dead. In 2018, Ace of Cups, the pioneering all-female San Francisco band she’d co-founded, was making a new album, and Kaufman invited Weir to sing on one of its songs, “The Well.” To Kaufman’s surprise, Weir spent several very focused days in the studio, singing, adding new guitar parts, and rebooting the song.

By then, Weir’s personal life had stabilized. In 1999, he had married his longtime girlfriend Natascha Muenter, with whom he had two daughters, Chloe and Shala (who goes by Monet, her middle name). Kaufman had last seen Weir in 2011, but the change was noticeable. “At that time, he was less healthy, but subsequently, it just seemed like everything in his life, the really important things, were more to the front,” she says. “He was valuing what matters in his own life.”

“Bob finally had a lead guitar,” Hart says of John Mayer. “He could relax. This took the weight off.”

LAST JUNE, JUST A MONTH after his final shows with Dead & Company at the Sphere in Las Vegas, Weir was already onto his new musical adventure. Onstage at London’s Royal Albert Hall, he and Wolf Bros — which also included Was, drummer Jay Lane, and keyboardist Jeff Chimenti — were refreshing the Dead repertoire, this time with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The show was the latest in a series of orchestral Wolf Bros gigs begun the year before. “He said the weirdest thing to me when we were taking our bows,” Was recalls. “He loved the sound of that room. The orchestra was great. And he said, ‘Man, I’d be happy to die in this place.’ I knew what he meant. But he didn’t know how it was going to resonate six months later.”

Wolf Bros began back in 2018. For what would be his last and most ambitious venture outside of the Dead, Weir unexpectedly reached out to Was, with whom Weir had occasionally worked over the previous two-plus decades. (Weir, a true believer in the messages conveyed in dreams, had dreamt of the late bassist Rob Wasserman recommending Was for the gig.) The idea, Was says, was to focus on Weir’s songs and the characters in them rather than on the jammy side of the Dead. In typical on-the-fly fashion, Weir told Was to learn six Dead songs — then promptly forgot which ones when Was showed up for the trio’s first rehearsal. “He just started playing what he felt at the moment,” Was says. “I think we jammed on a minor chord for 20 minutes.” When it stopped, Weir called his team and told them to book a tour; he’d already come up with “Wolf Bros” as the band name.

Dead & Company in 2025

© Jay Blakesberg

For the following seven years, when he wasn’t joining peers like Paul McCartney or Paul Simon onstage, Weir reinvented himself again with Bobby Weir and Wolf Bros. In such a spare setting, his unconventional guitar parts were more clearly and cleanly heard, and the shows felt like he was reclaiming his legacy outside of the Dead. (When Was suggested a few of Garcia’s songs, like “To Lay Me Down,” Weir passed: “There was definitely resistance. Too close to something,” says Was.) At Third Man Records in Nashville, as owner Jack White looked on, the band also cut an album, which included the first studio version of “Jack Straw.” (According to Was, the album, produced by Dave Cobb, was largely finished by the time of Weir’s death.) Late last year, Was received a text from Weir, relaying specific instructions about how to pare back the music even more and play fewer notes in the future.

In the last year or so of his life, Weir’s work revealed a sense of urgency. By last year, the Dead had lost many of its key members; Lesh, Barlow, and singer Donna Jean Godchaux had all died in the previous few years alone. According to Was, Weir would sometimes speak of death when the band was on the road. “He was acutely aware that time was running out,” he says. “Not as quickly as it actually did, but he was aware that he wasn’t going to be around forever to play these songs.” That, he says, was partly the impetus for arranging the Dead repertoire for symphonies: “He told Jay, Jeff, and me that his intention was for us to continue playing those shows when he couldn’t do it anymore.”

Last summer, the Dead celebrated their 60th anniversary at Golden Gate Park, which again confirmed Weir’s central role. Still not the most physically expressive character on stage, his satisfaction was clear to Lesh’s son Grahame, who joined the band for a few songs. “Bob would have this sort of little grin kind of behind the mustache,” Grahame says. But to Burbridge, the shows also revealed that Weir was coping with unspecified health issues. “He was moving very slow,” he says. “Everybody could see he was struggling. The fact he pulled it off was the highlight.” The future appeared hazy, too. Weir had been a road dog for so long — he even parked his tour bus outside of the Sphere despite renting a nearby home during the band’s run there — that the dearth of any live dates for 2026 was startling, almost alarming, to those in the Dead world.

Just before Christmas, members of Dead & Company, Weir included, reunited in a holiday-greetings group text. But according to those who knew or worked with Weir, his last few months were private ones as he dealt with his cancer. Hearing that his friend of nearly 60 years was in his final days, Hart visited Weir at his home in Mill Valley, California. “We went for a ride — he drove my car and seemed on the mend,” Hart says. “Then down the rabbit hole he went.” Those in the dark about the decline of Weir’s health were stunned when his family announced that he had “transitioned peacefully, surrounded by loved ones.”

“Bob said, ‘Man, I’d be happy to die in this place,’ ” Was recalls. “I knew what he meant.”

For both longtime Deadheads and those who’d discovered the band in more recent times, Weir’s passing wasn’t just the loss of another classic-rock hero. Although Hart and Kreutzmann remain, the disappearance of the last voice of the Dead felt cataclysmic. “There’s certainly a generation that has now grown up with Bob being their closest connection to that music, especially with Phil passing,” says Kaufman. “I know a lot of my friends and I are feeling extra emotional, because this thing is gone now. The front line is gone.” The future of Dead & Company is very much up in the air, but as Grahame Lesh says, “You can’t really replace Bob, and we’re going to find that out even more now.” Weir himself saw it coming, as he told Rolling Stone in 2016. During an early show with Dead & Company, he flashed to another scene. “It was 20 years later, and I look over to my right and John had turned gray,” he said. “I looked over to my left at Jeff and his hair was silver. Then I looked back at the drum riser and there were two kids back there, all holding forth and serving the music.” The vision then appeared in a dream that same night. “I awoke with the revelation that if we serve this legacy, it’ll just go on,” he said. “And people will be teaching this in music school in 200 or 300 years. That’s an edifying feel. But it also came with the responsibility of doing this right.”

You may be interested

Six-planet parade to light up the night sky – what you need to know

new admin - Feb 17, 2026Keep in mind that weather conditions and light pollution significantly impact stargazing (Image: Getty)Astronomy fans are set for a celestial…

‘Must see’ thriller so scary viewers walked out halfway now on iPlayer | Films | Entertainment

new admin - Feb 17, 2026BBC iPlayer has discreetly added a tense thriller that is so terrifying audiences were forced to leave the room midway…

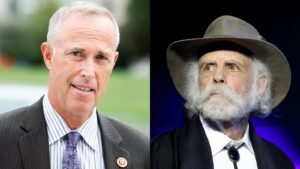

Rep. Jared Huffman Honors Bob Weir With Barefoot Tribute in Congress

new admin - Feb 17, 2026[ad_1] On Feb. 4, 2026, Bob Weir‘s spirit was present on the House of Representatives floor. Congressman Jared Huffman made…