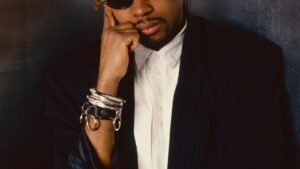

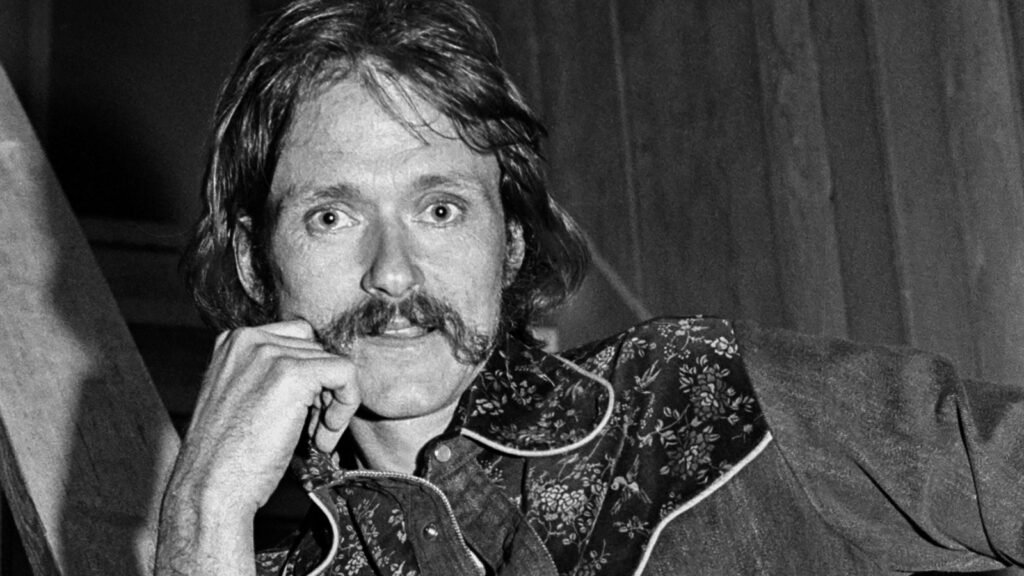

Jesse Colin Young Sang ‘Get Together,’ But Also Ran Weird Record Label

When Jesse Colin Young’s death was announced on Monday, it was inevitable that “Get Together” — the peace-and-brotherhood anthem that he and the Youngbloods turned into a decades-long radio staple —would be mentioned first. Young neither wrote it nor was the first to record it. But even after it’s been covered by everyone from Joni Mitchell and Jefferson Airplane to Kelly Clarkson, the Youngbloods’ version, with its snuggly harmonies and spiraling guitar, remains definitive, the most reassuring of them all.

That said, Young had more to offer than that song. His voice, sweet and silky but occasionally tough, was unique among his peers. Over the course of just under a decade, the Youngbloods transformed from a tough, spunky New York City bar band (heard on their 1967 debut, The Youngbloods) to mellow, stoner-friendly Marin County Americana predecessors (heard on later albums like Good and Dusty). Their Charlie Daniels-produced Elephant Mountain provided us with “Darkness, Darkness,” Young’s haunted song inspired by Vietnam soldiers, and “Sunlight,” the type of song that gave hippie serenading a good name at the time.

On his own, Young staked out a turf between light R&B, jazz, country, and rock & roll (he was like a less-volatile Dickey Betts) on albums like Song for Juli and Light Shine. Working at times with musicians who also backed the very demanding Van Morrison, Young stretched out on rambles like “Ridgetop,” and on The Perfect Stranger. He even wandered into yacht-rock territory — never mind that handlebar mustache.

Then there’s his and the Youngbloods’ other legacy — releasing some of the weirdest stuff ever rolled out by a major label in the history of music.

After “Get Together” became a belated hit two years after its release (it was the Lizzo “Truth Hurts” of its time), the Youngbloods took advantage of their newfound status and left RCA, their record company, for Warner Bros. At the time, rock & rollers were starting to launch their own labels, subsidized by majors. The Beatles’ Apple was the prime example, but soon after, the Rolling Stones had Rolling Stones Records, Jefferson Airplane had Grunt, and Led Zeppelin had Swan Song. It was a now unimaginable time when musicians could release whatever the heck they wanted, with no corporate interference whatsoever. The Youngbloods took full advantage of that freedom.

First considering Not So Straight as their label name, the band members ultimately chose Raccoon Records, and the weirdness started with Rock Festival, the band’s debut for Raccoon. Instead of a group photo, the cover art for their first live album was a bunch of pebbles (get it?). By then, the group had been reduced to a trio, and used their new, looser format to play long piano-fueled instrumentals and obscure folk songs. Rock Festival’s follow-up, Ride the Wind, featured a version of the title song that amounted to Marin County free jazz, with Young’s bass, Lowell “Banana” Levinger’s electric piano, and Joe Bauer’s drums ricocheting off one another for nine minutes — not typical destined-for-the-charts stuff. As a tribute to their new location, the Youngbloods’ next album, Good and Destry, included a remake of Merle Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee,” called “Hippie from Olema,” again, long before country was cool.

But that was just the beginning of Raccoon Records’ wild ride. Levinger put out an album of his own, Mid-Mountain Ranch, billed as Banana and the Bunch. On it, he indulged his love of bluegrass, country, and Chuck Berry, covering “Back in the USA” years before Linda Ronstadt revived it. Raccoon signed a bluegrass band, High Country. And then came Crab Tunes, credited to Noggins (Levinger, Bauer, and new Youngbloods bassist Michael Kane). Simply one of the most baffling records ever released, it was two sides of formless shronk noodling that, as I can attest, sent Billy Joel-loving college students questioning their roommates’ musical taste and sanity at the time.

Raccoon also released two albums by the willfully underground troubadour Michael Hurley. At a time when singer-songwriters were in vogue, Hurley was technically in that pocket. But his prematurely craggy voice and melodies, combined with arrangement rooted in string bands, were nothing like the soft-rock dudes on the radio; if anything, Hurley was acid folk. Only Hurley could write a poignant song, “Werewolf,” about the inner torment of a wolfman. Cat Power liked it so much she covered it on You Are Free.

Given the determinedly oddball nature of its releases, it was no surprise that Raccoon didn’t last long, going the way of Apple, Grunt, and all the rest. Except for one of Young’s own albums, Together, you won’t find any of its output on streaming services. But Raccoon helped pave the road for later musicians like Phoebe Bridgers, Jack White, Jay-Z, and Eminem to start their own (and more fiscally viable) labels attuned to their sensibilities.

And last fall, Hurley played a set to a hushed, reverent audience at the annual Brooklyn Folk Festival. Much like the critters it was named after, Raccoon went into a long type of hibernation — called “torpor” in their case — but left behind a quirky trail all its own.

You may be interested

Soccer fan dies after fall during Nations League final between Spain and Portugal

new admin - Jun 09, 2025MUNICH — A soccer fan died during the Nations League final between Spain and Portugal on Sunday after falling from…

Warner Bros. Discovery is splitting into two companies

new admin - Jun 09, 2025Warner Bros. Discovery has announced plans to split itself into two companies, separating its streaming and studios divisions from its…

Riley Gaines says Simone Biles ‘tarnished’ her reputation in ‘2 tweets’

new admin - Jun 09, 2025[ad_1] NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles! Riley Gaines broke down the personal attack Simone Biles levied on…